Usability Testing of Medical Devices

Are you bringing a new or modified medical device to the US Market? Then you probably know there are guidelines from FDA and standards from ISO that have to be followed to demonstrate that your product is safe and effective to use for the intended users in their intended use environments.

What is the FDA guidance for medical device usability?

FDA requires usability testing, which is called human factors validation testing, "to demonstrate that the device can be used by the intended users without serious errors or problems, for the intended uses, and under the expected use conditions.”

This blog gives you a basic understanding of the steps and processes involved in the FDA human factors guidance, which sets forth the following requirements:

- Test participants represent the intended (actual users) of the device.

- All critical tasks are performed during the test.

- The device user interface represents the final design.

- The test conditions are sufficiently realistic to represent actual conditions of use.

Identify actual users for medical devices

To identify your actual users, you need to consider all types of users who will engage with the product, such as patients, professional and lay caregivers, doctors, and service technicians. Each type of user represents a user group. User groups are defined by their engagement with your product and their knowledge, training, or experience with devices like yours.

Here are two examples of the user groups for a human factors validation study.

Example: Cardiac monitoring device

This cardiac monitoring device is to be prescribed by a doctor for patients to use in their home over a period of weeks, in which cardiac monitoring will take place, then returned to the medical device manufacturer for cleaning, inspection, and subsequent reuse. The following three user groups are identified:

- Adult patients who may or may not be experiencing cardiac-related symptoms – these users can be combined into one group, so long as it includes users with no current symptoms (to represent general population), as well as users who have experienced cardiac symptoms.

- Health care professionals (HCPs), including nurses and certified medical assistants who will train the patient in how to use the device at home – these users can be combined into one group, so long as all participants have the same type of experience with similar products in setting up and monitoring electrophysiology and cardiac devices for patients.

- Technical staff who will prepare the device to send out to patients and receive returned devices to prepare for reuse – this is a single user group of technicians with experience reprocessing devices for reuse. If the device manufacturer receives its devices for reprocessing in their facility, then employees of the device manufacturer can be recruited for the study; if the device is reprocessed in a clinical setting, technical staff would need to be recruited from the types of hospitals and clinics where similar devices are reprocessed.

Example: Endovascular stent graft

This device is a stent graft to be inserted by a physician for the endovascular treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. The single user group comprises vascular surgeons and other cardiovascular clinicians who have experience performing this type of surgery.

For each user group, a “screener” needs to be developed. The screener provides the criteria for selecting or rejecting potential participants.

Identify training requirements for medical device users

Once the user groups are identified, training requirements need to be determined. If training for any of the user groups is expected, then training should be included in the study. If training is expected but may not be available in actual use in all cases, a worst-case scenario could be identified to conduct testing without training. In this case, a separate, untrained user group may be needed for the study, along with a user group that receives training.

Generally, when training is expected, a qualified trainer (nurse, company representative) who represents the training that will be provided in real life needs to provide the training in the testing situation. For example, patients are generally trained for in-home use of a medical device by the nurse who prepares them to go home after a hospitalization. The nurses have to be trained so that they can then train the patients.

Nurses are often trained in small groups, representing the in-service training sessions they would likely receive by the device manufacturer’s representative. Physicians are typically trained individually by a company sales representative or technical support staff.

Plan for the decay period

When training is part of the process for preparing users to use the medical device, the training needs to be provided in advance of the testing session. Importantly, a “decay period” needs to be included to provide a break between the training session and the testing session.

FDA does not specify the length of the decay period, but it suggests that one hour may be acceptable in some cases. In fact, a minimum one-hour decay period is commonly used in practice, as reflecting what could be a user’s lunch break.

If more time can be scheduled between training and testing, the better the realism of the training/testing scenario will be. However, it may be challenging to recruit some clinicians, such as skilled surgeons, to schedule time for training, followed by a break of a day or a week or more, and then schedule another time for the testing session.

How we handle the decay period

In our practice, we schedule each physician in their own training session, followed by a break of one hour on the same day, and then their testing session. Participants receive an incentive for their total time for the study, which includes training, decay period, and testing.

For nurses, we schedule 3 or 4 participants for an in-service group training in the morning, then provide a minimum of a 1-hour decay period break, after which we schedule the nurses in back-to-back individual sessions in the afternoon and evening of the same day.

Fewer cancellations result when all 3 elements – training, decay, testing - are included in the same day.

Identify all critical tasks for medical device testing

For each user group, all critical tasks must be identified and validated. A critical task is defined in the FDA guideline as “a user task which, if performed incorrectly or not performed at all, would or could cause serious harm to the patient or user, where harm is defined to include compromised medical care.”

Critical risks can be evaluated through performance tasks and knowledge tasks. For performance tasks, validation studies document the number of use errors, close calls, and difficulties experienced by users. For knowledge tasks, these studies document the users’ understanding of safe use of the product beyond what can be observed in actual use. Knowledge tasks typically include questions around critical risks, such as proper storage, disposal, and reuse. A knowledge-task question might be, “How long can you safely store the device?” or “What conditions are required for safe storage?” Knowledge tasks generally require the user to find the information in the instructions for use (IFU) or in the labeling or packaging, or in recall from training or experience.

The critical tasks are derived from the URRA (Use Related Risk Analysis). The FDA identifies use-related risk based on “the combined probability, occurrence, and severity of harm.”

A URRA sets forth the systematic use of available information to identify use-related hazards and to estimate use-related risk. To do that, regulatory compliance staff at the medical device manufacturer need to establish levels of severity (typically on a scale from 1 - negligible to 5 - catastrophic) and frequency and likelihood of occurrence for each task. Those tasks identified as serious (3 or higher severity) are determined to be critical tasks.

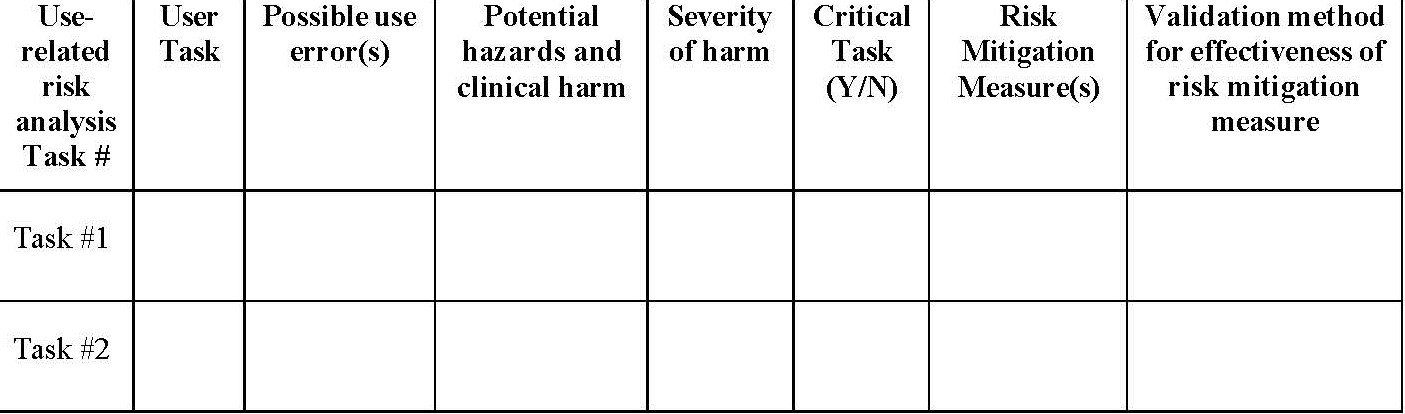

A new FDA Draft Guidance document (December 9, 2022) provides the following table for use in presenting the critical risks identified in the URRA. The last column, the validation method, is generally indicated as the use scenario/performance task # or knowledge task #. These numbers come from the test plan included in the test protocol.

Recruit participants for medical device testing

Once the user groups, session lengths based on critical tasks, and training requirements are determined, recruiting can begin, using the screeners developed for each user group.

Recruiting participants for studies is one of the most important and challenging parts of planning for usability testing, as some participants may be difficult to locate and recruit, while others, such as specialized surgeons, may require hefty incentives to secure their commitment to participate.

If you do not have the resources to recruit the participants yourself, you will need to work with a company that specializes in recruiting participants that meet your requirements. It is important to note that participants cannot be employees of the device manufacturer, except where the user group is exclusively employees (such as service technicians used in reprocessing devices). It is also important to note that participants must be U.S. residents.

For each user group, FDA recommends a minimum of 15 completed usability testing sessions. This means that you will need to recruit and schedule additional users (generally 18 – 20 participants per user group) to allow for cancellations while still meeting the 15-person minimum.

Develop the test protocol for medical device usability testing

Once you have done the planning to identify user groups, training requirements, and the critical tasks, you can document all aspects of the human factors validation test in a test protocol. Topics typically include the following:

- Device description

- Study purpose

- Primary test data (key event definitions, event detection methods, participant’s subjective feedback)

- Test method (typically simulated use)

- Test participants (recruiting, compensation, identify protection)

- Test environment (location, testing space configuration, lighting and sound levels, distractions)

- Test materials (device, instructions for use, labeling/packaging, and other peripheral materials needed for testing)

- Test administration (moderator and notetaker)

- Test agenda (scenarios of use, knowledge tasks, post-task questions, post-study interview)

- Data collection method (data recording form)

- Data analysis method (typically observation and subjective feedback, used to determine root cause for critical risk errors)

- Test report deliverable (based on FDA’s Guidance, Table A-1, Outline of HFE/UE Report, Section 8: Details of Human Factors Validation Testing)

- Appendices:

- Screener(s)

- Moderator’s Guide(s)

Test protocols can vary widely, and many device manufacturers have templates in place for both the test protocol and the test report. In this primer, I will focus on a few key topics in the test protocol.

Use scenarios

For the procedural/hands-on part of the study, a use scenario provides context for the user. The use scenario describes a situation that results in the participant interacting with the medical device in a natural workflow. For example, a use scenario for a clinician using a cardiac monitoring device and the associated app, might be this:

“You are preparing to see your patient [patient name with patient information provided in a handout], who will be fitted with a cardiac monitoring device. In preparation for seeing the patient, use the app on the mobile device [provided as part of the study] to confirm the patient’s details in the mobile application.”

Simulated use

The medical device needs to be in a production-ready state, but the device itself may need to be modified for simulated use to protect the participants from any risk while using the device. Simulated use may also be needed to provide realistic, but not actual data on a patient. Simulated use may include the use of a manikin in place of an actual patient or it may include a person recruited to take the role of the patient.

Simulated use also means that the testing environment must simulate, to the extent possible, the environment in which the device will be used. For instance, if there are noises in the environment, such as voices or the sounds of equipment in a clinical setting or music in a home setting, these can be simulated with an audio recording of the conversations and equipment sounds in a clinical setting or a music track playing music for a home settng. If lighting conditions will be low in actual use, these should be simulated. If the space in actual use is constricted, similar space restrictions need to be set up for simulated use.

Some products are best tested in a simulated use surgical suite, which some recruiting companies can provide in their testing suite. In most cases, this requirement is not needed if the test protocol documents how the simulated environment will be set up. For example, a hospital bed for a participant or a draped table with a manikin representing the patient can be used.

Key event definitions

All use errors for all critical tasks must be identified for later analysis.

FDA defines a use error as “an action or lack of action that was different from that expected by the manufacturer and caused a result that (1) was different from the result expected by the user and (2) was not caused solely by device failure and (3) did or could result in harm.”

In addition to identifying use errors, FDA wants to know about any close calls or difficulties observed and experienced by users. These are not defined as use errors, but the study needs to identify and analyze them, particularly when more than one user experiences a close call or difficulty. The test protocol needs to define a close call or difficulty, along these lines:

- Close call - a case in which a participant almost commits an error, but “catches” himself or herself in time to avoid making the error. The term also describes a case in which a participant commits a use error but detects it quickly and recovers before the error becomes consequential.

- Difficulty

- a case in which a participant appears to struggle to perform a task. Such a struggle might be indicated by multiple attempts to perform the task, anecdotal comments about the task’s difficulty, facial expressions suggesting frustration or confusion, and higher than usual task performance times.

Other key definitions typically include:

- Assistance needed – a case in which a participant requires or requests assistance to complete a task. Considered a task failure in cases where it does not represent an intended use outcome. In cases where customer support is available, requests for assistance would be noted and analyzed as to root cause, but would not be noted as a task failure.

- Test artifact – an error or omission that results from the simulated-use conditions employed in testing, which are not consistent with actual use.

Moderator's guide

A moderator's guide (also called a Facilitator's Guide) is needed for each unique user group. The guide provides a script for the moderator to use in each testing session. The script includes the welcome, introduction to the study, pre-test questions about the participant’s experience/background, the scenarios/task flows being tested, post-task questions, root cause analysis for any use errors, close calls, or difficulties observed, and post-study interview questions.

The uniformity of sessions is achieved by the moderator's close adherence to the guide.

Conduct medical device usability testing sessions

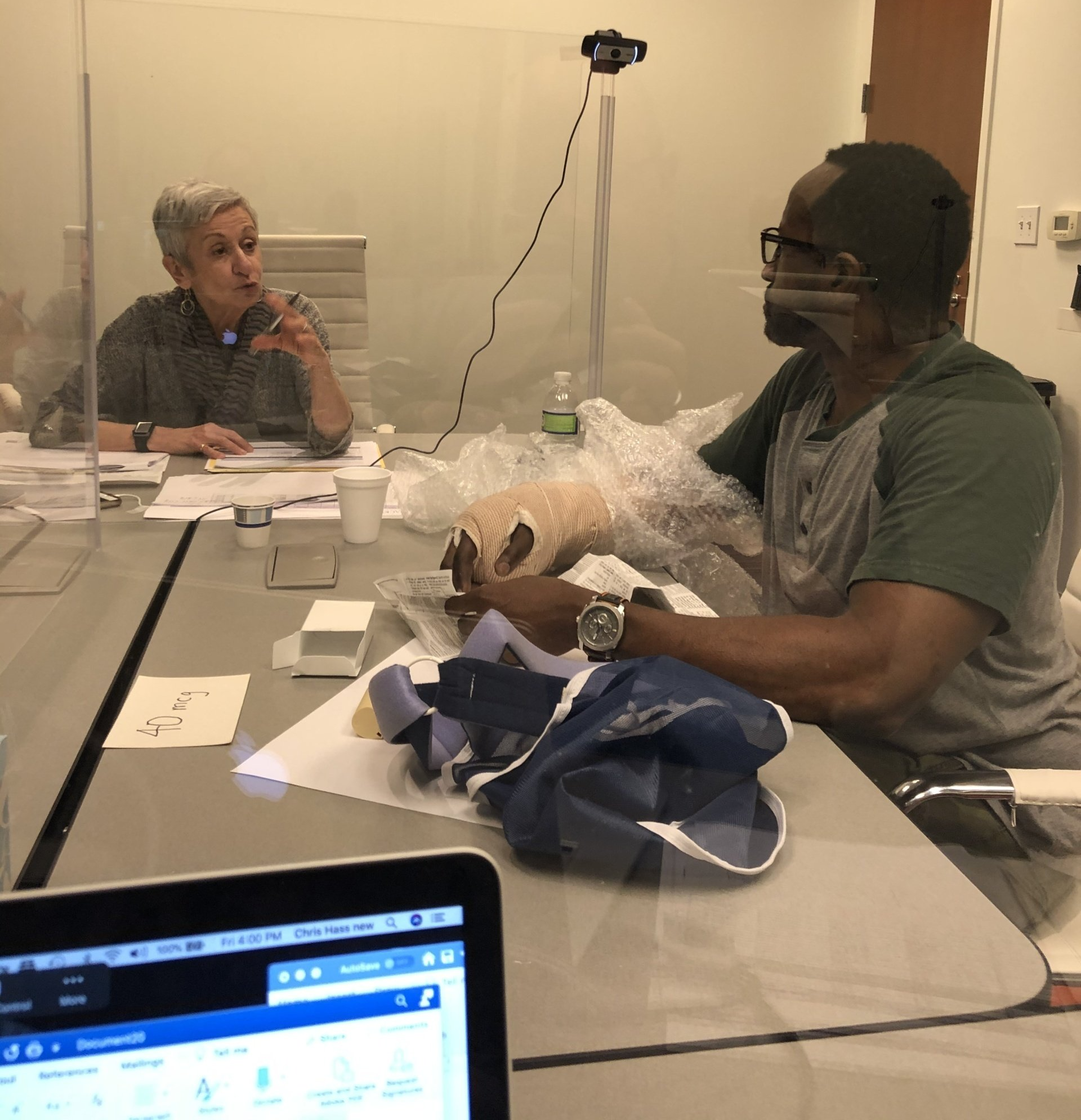

The best practices for human factors validation testing puts the test protocol plan into action in individual test sessions with each user in every user group.

Testing sessions (which typically can be as short as 15 minutes or as long as 2 hours or more) provide the user experience required to determine whether the device is safe to use. The logger/notetaker uses the logging template (typically in the form of an Excel spreadsheet) to note use errors, close calls, difficulties, and any assistance needed for all critical tasks, responses to knowledge-task questions, and participants’ answers to post-task questions and post-study interview questions.

For the post-study interview, FDA suggests the following questions:

1. What did you think of the device overall?

2. Did you have any trouble using it? If so, what kind of trouble did you have?

3. Was anything confusing?

4. Please tell me about this [use error or problem observed]. What happened? How did it happen?

In our studies, we typically ask Question 2 and Question 2 above as part of post-task subjective feedback. Then we conduct root cause analysis for subjective feedback from participants on our observations of any use errors, close calls, difficulties, or incorrect answers to knowledge-task questions. Then in the post-study interview we focus on the participant’s overall experience with questions like the first one in the FDA bulleted list above, as well as these questions:

- Would this device support your work? Yes/no. Explain.

- Is there anything you would change?

- Do you have any final thoughts you would like to share?

Write the report for FDA submission

Now that testing is complete, the job of documenting the findings to determine the root cause for all use errors, close calls, or difficulties observed for critical tasks and non-critical tasks in the task flow requires a review of the findings and root cause analysis based on the notetaker’s notes and any notes taken by the moderator and observers.

The report provides quantitative findings, counting how many participants experienced each use error, close call, and difficulty, and any incorrect responses to knowledge-task questions. For each error, close call or difficulty and each error in answering a knowledge-task question, the report provides an analysis of the cause of the error to determine the root cause. The report also provides subjective data in the form of relevant comments made by participants with respect to each critical task in which a use error, close call, or difficulty was discussed, as well as participants’ subjective feedback in the post-study interview.

How to report use-related risks and mitigations

FDA states that “the primary purpose of the analysis is to determine whether [any] part of the user interface could and should be modified to reduce or eliminate the use problem and reduce the use-related risks to acceptable levels. An essential secondary purpose of the analysis is to develop a modified design that would not cause the same problem or a new problem.”

Changes to the device design and any associated elements are called “mitigations,” as they are intended to reduce the errors noted.

However, FDA does not expect that every use error can be addressed by mitigation. If, for example, the user did not read the instructions during testing, resulting in a use error or an incorrect answer to a knowledge-task question, the moderator will want to explore the participant's actions in the post-task or post-test interview. The moderator may ask the participant to read the relevant step in the instruction. The participant may state that the instruction was clear, but they chose not to read it. The goal of the analysis of root causes of errors is to minimize the risk as far as possible. In this case, there might not be any further mitigation possible.

In other cases, the report may indicate that minor changes to the IFU or labeling, such as adding directional arrows to the interface, can aid the user's understanding of what they need to do, whether or not they read the instructions. A minor change such as this addition, it can be argued, does not require retesting.

How to decide when to re-test

Mitigations are often presented as changes needed to the instructions for use, labeling, or training. When numerous issues are identified, FDA will likely expect that further testing is needed to confirm the reduction of risk following mitigation.

In this situation, the current human factors validation test becomes a formative usability test. Retesting in a follow-up summative human factors validation study need only focus on the critical tasks that received a high number of issues in the current test.

Timeline considerations

When preparing for FDA

human factors validation testing for medical devices, this introduction gives you a general idea of the process. The actual steps in planning, preparing, testing, analyzing the findings, determining root causes for critical task failures, and writing the report take time and require many more considerations than I can cover here.

How much time? On a fast track for a study with a single user group in testing sessions of one hour or less, the timeline can be completed in 10 weeks if everything is ready at the start of the planning process and the team can focus full attention on the requirements. For testing with more user groups or in longer sessions, the timeline will likely be extended.

Want more practical insights? Check out these blogs.

Carol Barnum

Carol brings her academic background and years of teaching and research to her work with clients to deliver the best research approaches that have proven to produce practical solutions. Carol’s many publications (6 books and more than 50 articles) have made a substantial contribution to the body of knowledge in the UX field. The 2nd edition of her award-winning handbook Usability Testing Essentials is now available.